Equity Myth Buster: “Rich Neighborhoods Get All the Flood-Mitigation Funding”

A myth being promulgated in Harris County Commissioners Court and certain low-to-moderate income (LMI) watersheds these days goes something like this:

- The FEMA Benefit/Cost Ratio (used to rank grant applications for flood-mitigation projects) favors high-dollar homes.

- That disadvantages less affluent, inner-city neighborhoods compared to more affluent suburbs.

- Therefore, less affluent neighborhoods get no help and the more affluent neighborhoods get it all.

This post busts that myth. But it won’t stop activists from demanding more “equity.”

If you look at all flood-mitigation spending in Harris County since 2000, on average, less affluent watersheds already receive 4.7X more partner funding per watershed than their more affluent counterparts.

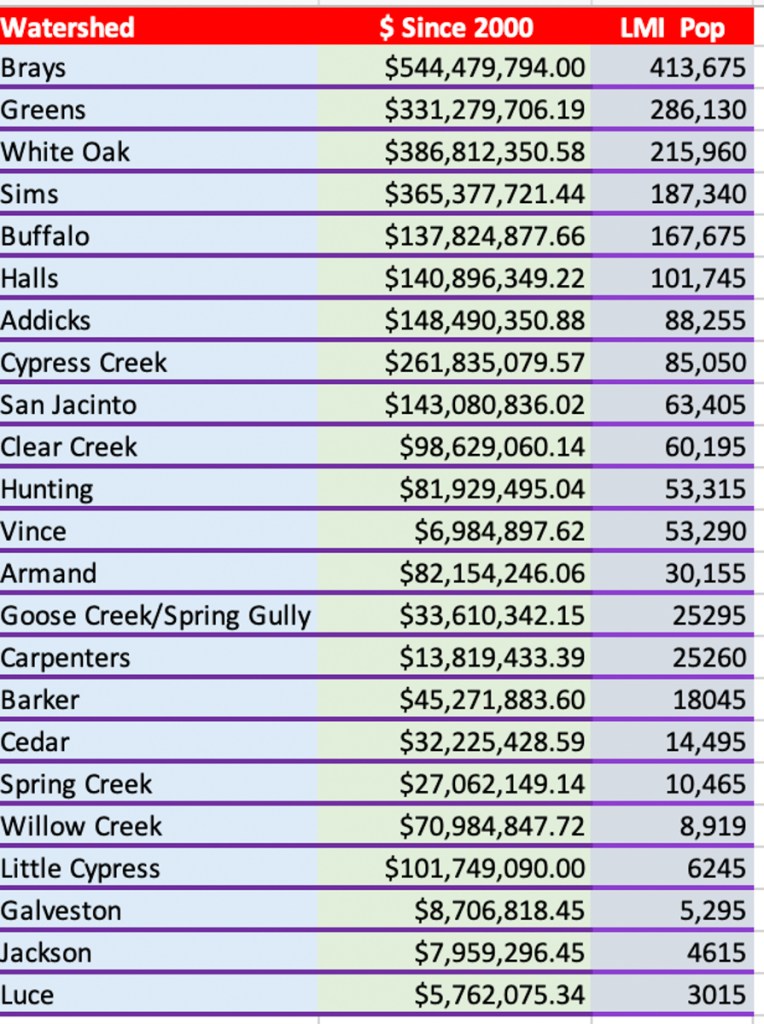

Analysis of data obtained via FOIA request

Myth Ignores Other Factors, Frequently Leaps to Wrong Conclusions

Like much of political discourse these days, the myth focuses on a narrow sliver of truth, ignores other factors, and frequently leaps to the wrong conclusions.

An analysis of Harris County Flood Control District data going back to the start of this century shows how far off the myth can be.

There are dozens of different ways to slice and dice the data. I’ve looked at most of them and validated “dollars invested” with aerial photography.

Today, I focus on partner grants because they represent such a huge percentage of the flood-bond budget and because there is so much misinformation floating around about them.

And I will look at partner funding from the standpoint of outcomes, not just processes (as in the myth).

Methodology for Analysis

For this analysis I obtained Harris County Flood Control District spending data between 1/1/2000 and 9/31/2021 via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. I requested the data by watershed, decade, pre-/Post Harvey, source of funding (local vs. partner), and type of activity (i.e., engineering, right-of-way acquisition, construction and more). I cross-referenced this with other data such as flood-damaged structures, population, population density, and percentage of low-to-moderate income (LMI) residents.

When considering grants, the percentage of LMI residents in a watershed takes on special significance. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants often require high percentages of LMI residents in the area under consideration.

In the charts below, you will see references to watersheds with LMI populations above and below 50%. Above 50% means more than half the residents in the watershed have an income LESS THAN the average for the region. Below 50% means more than half the residents earn more than the regional average.

Harris County has 23 watersheds. Eight have LMI percentages above 50% (less affluent). Fifteen have LMI percentages below 50% (more affluent).

When reviewing the charts below, pay particular attention to the italicized words: Total, Partner, and On Average. They represent three different ways to look at the same question: Do housing values disadvantage an area when applying for grants?

For this analysis, I focused only on the long term, since decisions on more than a billion dollars in flood-bond grants are still outstanding.

FOIA Analysis Contradicts the Popular Myth

One of the first things you notice when you look at watersheds above and below 50% LMI, is that the eight least affluent watersheds have gotten more than 60% of all dollars actually spent on flood mitigation since 2000.

Because the allegation was that partnership grants favored affluent areas, I then analyzed whether partner dollars went mostly to affluent or less-affluent watersheds. The answer is less affluent…overwhelmingly.

The last observation by itself is telling. But because of the widely different number of watersheds in each group, I also wanted to calculate the average partner dollars per watershed in each group. This blows the “rich neighborhoods get all the grants” argument to pieces. Less affluent watersheds got, on average, 4.7X more.

This busts the myth. But digging even deeper into the data reveals two things: wide variation between sources of funding and within LMI groupings.

USACE Funding Skews Partner Totals

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) accounts for much of the partner funding. USACE has provided significant funding for projects in the Sims, Brays, White Oak, Hunting, and Greens Bayou watersheds. The Clear Creek watershed will also soon see work on a new USACE project. USACE has completed its planning process and proved positive benefits to national economic development. That made projects worthy of Federal investment.

Halls Bayou: Digging Deeper

The Halls Bayou watershed also went through the USACE planning process, but the results did not show enough flood-damage-reduction benefits to outweigh the costs of the proposed projects. Thus, the Halls Bayou watershed currently has no USACE-funded projects.

Despite that, Halls has received more partner funding than 16 other watersheds since 2000. Only two watersheds in the affluent group of 15 received more partner funding. See the table below.

USACE also evaluated the more affluent Buffalo Bayou; results showed that costs outweighed the flood-damage-reduction benefits there.

Despite Halls having the highest percentage of LMI residents in Harris County, Halls has received more total funding and 2.5X more partner funding than Buffalo Bayou in the more affluent group.

FEMA Considers More than Home Values, Not All Grants Come From FEMA

While it’s true that FEMA considers housing values as a factor in benefit/cost ratios, benefit/cost ratios (BCRs) also consider factors such as:

- The number of structures damaged

- Threats to infrastructure

- Proximity to employment centers

- Need for economic revitalization

- Percentage of low-to-moderate income residents in an area

- Number of structures that can be removed from the floodplain by a project.

And not all grants come from FEMA. For instance:

- HUD offers 15 different types of grants. Many favor distressed neighborhoods and HUD often offers a 90:10 match.

- Texas Water Development Board Grants have their own criteria.

- USACE funds dozens of different types of flood-mitigation programs. Many support national defense, the national economy, strategic interests, the environment, commerce and navigation.

So don’t settle for soundbites. They often mislead.

Posted by Bob Rehak on 12/30/2021

1584 Days since Hurricane Harvey