Is Downstream Flood Mitigation Keeping Pace with Upstream Development?

5/14/25 – This morning, I gave a presentation that compared the pace of downstream flood mitigation with the pace of upstream development. Are we gaining or losing ground in the Lake Houston Area?

Presentation Connects Many Dots

Answering that question requires connecting many dots. Here are the slides from the presentation with my narrative.

Offsetting Forces

As new upstream development adds impervious cover (roads and roofs) that can increase and accelerate runoff, building flood peaks higher and faster. And that can erode the safety of downstream residents. Managing flood risk becomes a struggle between competing forces.

MoCo One of Fastest Growing Counties in Country

The Lake Houston Area lies downstream from one of the fastest growing counties in the country. Montgomery County (MoCo) grew 68% in the last 15 years and 4.8% in 12 months recently. MoCo is currently the seventh fastest growing county in the entire country.

Ryko Exemplifies Danger of Upstream Development

Let’s look at a proposed MoCo development in the headwaters of Lake Houston. A company named Ryko bought 5,500 acres about a quarter mile west of Kingwood. It’s in the southern part of a triangle formed by Spring Creek, the San Jacinto West Fork and the Grand Parkway.

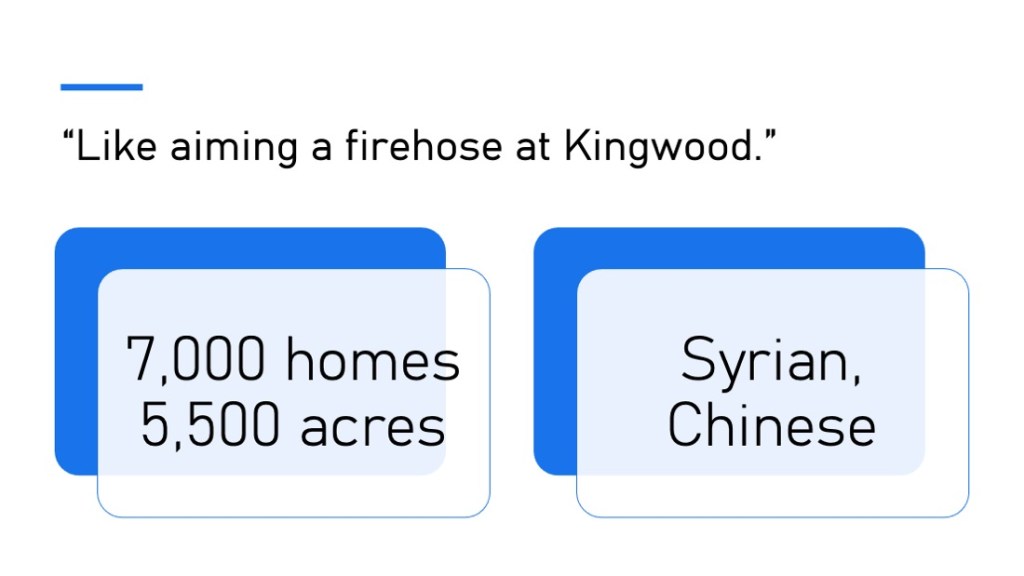

“Like Aiming a Firehose At Kingwood”

Ryko, which is a Syrian-owned company, is reportedly working with Wan Bridge, a Chinese company, to develop 7,000 homes on the property. One of the leading hydrologists in the area told me that developing this property would be “like aiming a firehose at Kingwood.”

Many “Guardrails” Being Removed

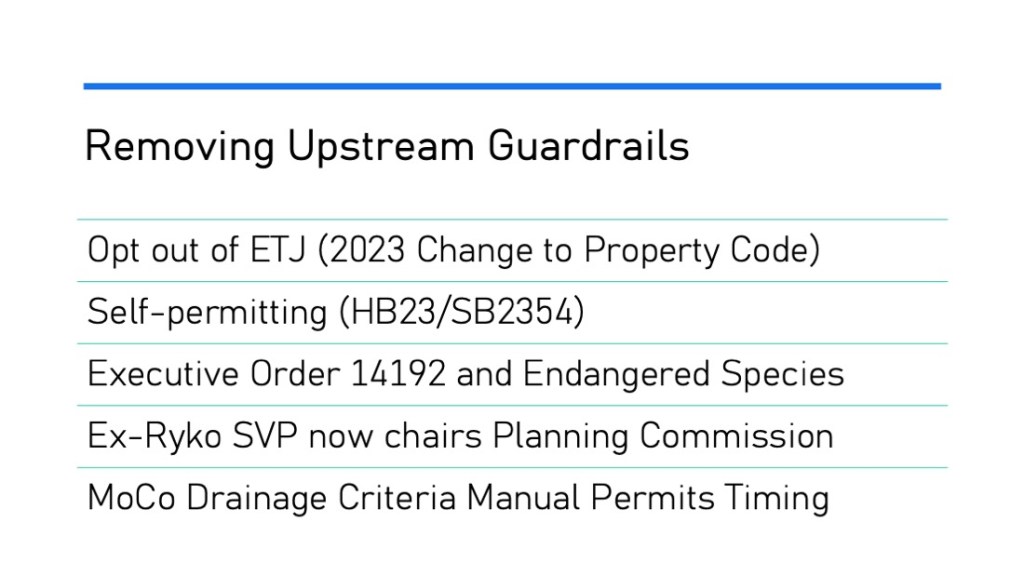

Government has established many guardrails over time to protect people from insufficiently mitigated upstream development. But many of the guardrails are being removed. Or people are trying to remove them.

In this case:

- A change to the state property code in 2023 gave developers the right to opt out of a city’s extra territorial jurisdiction (ETJ). ETJs lay the groundwork for future annexation by ensuring new infrastructure meets the standards of areas that might annex them someday. But if developments are not in an ETJ, they could change plats without approval.

- Two bills pending in the legislature, HB23 and its companion SB2354, would essentially let developers “self-permit” by hiring engineering firms that replace government oversight.

- The Endangered Species Act (ESA) constrains development in areas inhabited by threatened or endangered species. But Executive Order 14192 could change that. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed a change under the order that means Ryko would no longer have to work around endangered species on its property.

- An ex-Senior VP of Ryko for 21 years is now chair of the Houston Planning Commission. She still reportedly represents the company as an independent consultant,

- The Montgomery County Drainage Criteria Manual hasn’t had a serious update for 40 years. The County still allows controversial practices, such as hydrologic timing surveys, to “prove” that upstream developments have no adverse impact on downstream residents.

Let’s take a closer look at the Ryko property with these issues in mind.

Upstream Development Almost Entirely in Floodplains

With that as a backdrop, what’s going on with the Ryko land? The map in the background for this next slide comes from Ryko’s Drainage Impact Analysis. It shows that their property (outlined in red) lies at the confluence of four major streams. All that blue represents floodplains and floodways.

How Bad Is Ryko’s Flood Risk?

FEMA’s base-flood-elevation viewer shows that at the southern end of Ryko’s property, any homes would be under 25 feet of water in a 500-year flood (18.7 feet in a 100-year flood). Even at the higher elevations farther north, homes would be under 7 feet of water in a major flood.

Frequent Bald Eagle Sightings

Homeowners father north report frequent sightings of bald eagles. They believe the eagles live on Ryko’s property which is currently wilderness. One resident sent me a video of two eagles that landed in a tree right outside her living room window.

How Developers Document “No Adverse Impact”

The Texas Water Code contains a rule that states upstream development can have “No Adverse Impact” on downstream neighbors. To prove no adverse impact, engineers compare estimated pre- and post-development runoff.

If post-development estimates are less than or equal to pre-development, they satisfy the requirement.

Estimates Based on Hydrologic Timing Not Always Accurate

But how accurate are those estimates? Montgomery County’s antiquated drainage criteria manual still lets engineers use hydrologic timing surveys, a practice now prohibited by the City of Houston and Harris County for several reasons.

Timing studies let developers avoid building detention basins if they can show that their development’s stormwater “beats the peak” of a flood. The theory: they aren’t adding to the peak.

Not building detention basins saves developers money and adds to the number of salable lots. But “beat the peak” studies have serious limitations and can often mislead.

They assume, for instance, a uniform storm across an entire watershed. But that rarely happens. Imagine the case of a storm like Harvey, which approaches from the south as developers to the north rush to get their water to the river. God help the people caught in the middle.

Timing surveys, in the case of Montgomery County, are also based on decades old data that ignores the cumulative impacts of other developments over time.

How Avoiding Detention Can Add to Flood Peaks

What often happens in reality is that you get higher peaks than if you had built detention. This graph shows three lines. The two at the bottom show typical pre- and post-development runoff rates where/when hydrologic timing studies are prohibited.

The height difference could be the difference between flooding or not flooding.

MoCo Still Doesn’t Require More Reliable Method

In short, building stormwater detention is a sure thing. Hydrologic timing is not.

Banning hydrologic timing studies would force developers to design systems that TRULY detain and slow runoff. But Montgomery County still permits timing studies. The County’s new Drainage Criteria Manual that prohibits them has been sitting on the shelf for more than a year.

Downstream Mitigation Slowing

Now, let’s look at what downstream residents are doing to offset the impacts of upstream development.

Compared to the period after Harvey, that activity has slowed. The Lake Houston Area Task Force identified three crucial needs to reduce flood risk.

- Dredging to increase throughput

- More floodgates on Lake Houston to speed up output

- Upstream detention to reduce input.

Dredging is Highlight to Date…

Dredging continues. We’ve spent approximately $200 million to date and that total is still increasing.

…But More Sediment Keeps Coming

After the Army Corps finished its emergency West Fork Dredging Project, they recommended regular maintenance dredging to ensure our rivers had sufficient conveyance and our drainage ditches were not blocked. State Representative Charles Cunningham authored HB1532 to create a dredging district for the Lake Houston Area.

HB1532 passed overwhelmingly in the House and is now waiting to be heard by Senator Paul Bettencourt’s Local Government committee in the Senate.

But this legislative session ends in two weeks. Any bill not out of committee by this Friday is effectively dead. And Bettencourt has not yet scheduled Cunningham’s bill for a hearing.

Construction on More Floodgates Not Likely Before 2027

The additional floodgates on Lake Houston have been delayed repeatedly for various reasons. Simultaneously, the Coastal Water Authority (CWA) is looking at the costs of repairing the dam and replacing it altogether. The 70+ year old dam is near the end of its useful life.

CWA board member Dan Huberty stated that engineering for additional gates should be complete by 2027. At that time, the project will go out for bids.

The CWA won’t receive preliminary reports on dam repairs and replacement until at least July of this year.

No Progress on Upstream Detention, None Likely Anytime Soon

Meanwhile, virtually nothing has happened yet in terms of upstream detention. The San Jacinto River Authority identified 16 areas for upstream detention basins/lakes in its River Basin Master Drainage Study.

SJRA has no construction funds. So many of the projects were incorporated into the state flood plan. But the state’s Flood Infrastructure Fund does not have a committed revenue stream.

The Texas Water Development Board has about a billion dollars currently available to build $54 billion worth of requests in the flood plan.

So keep the pressure on elected representatives who can protect your family.

Posted by Bob Rehak on 5/14/25

2815 Days since Hurricane Harvey